WE know that Antinous died when he was barely 20 ... but a shocking new report says many young men were dead by that age ... and the common folk in Ancient Rome were lucky to reach age 30.

A

groundbreaking study of 2,000 ancient Roman skeletons from the time of

Antinous has shown how many of the ancient city's inhabitants were

riddled with arthritis, suffered broken bones and generally died in

their twenties.

The

harsh realities of life in imperial Rome were revealed by a

multi-disciplinary study carried out by an Italian team of osteopaths,

historians and anthropologists which used modern scanning techniques to

analyze a huge sample of skeletons recently unearthed in the suburbs of

the Eternal City.

The

skeletons were exhumed over the last 15 years in the course of

construction work on a new high speed rail line between Rome and Naples

and show the brutal reality of life for the majority of ancient Romans.

"The

bones are the earthly remains of poor, working-class Romans, taken from

commoners' graves, and display high incidences of broken and fractured

bones, chronic arthritis and high incidences of bone cancer," medical

historian Valentina Gazzaniga told The Local.

"What's

interesting is that the average age of death across the sample group

was just 30, yet the skeletons still display severe damage wrought by

the extremely difficult working conditions of the day."

The

research paints a grim picture of the dangers faced by ancient Roman

workers between the first and third century AD, with broken noses, hand

bones and collar bones all being commonplace injuries.

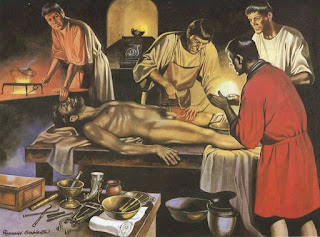

However, the scans also revealed that the city's ancient inhabitants were adept at treating such injuries.

"With

fractures and breaks so frequent, the Romans developed effective

solutions to treat them. The scans show that these rudimentary medical

techniques allowed people to keep working for years after sustaining

severe breakages," explained Gazzaniga.

The treatments might have been effective, but they were not pretty. Today,

severely broken bones can be surgically reset and bound in plaster, but

the Romans simply placed a wooden cage over the limb to immobilize it

until the shattered bones eventually fused themselves back together.

Aside

from bearing the scars of lax workplace safety, the scans also revealed

the back-breaking labour citizens had to endure for hours on end.

"Chronic

arthritis around certain areas such as the shoulders, the knees and the

back is present in the skeletons of those who died as young as 20,"

Gazzaniga explained.

The life of the average Roman worker bears a stark contrast to the good health enjoyed by the city's noblemen and Patricians.

A similar study carried out on the petrified Roman skeletons of Pompeii revealed the good health enjoyed by its citizens ... until they were buried by the erupting Vesuvius.

The

rich inhabitants in Pompeii ... a city of expensive villas and plush

domuses ... generally avoided hard labour and ate a varied diet.

But what about the working class Romans?

"It's

difficult to reach any specific conclusions about their diet based on

the results ... but given the incomplete way their bones healed and

really high incidences of bone cancer we encountered, it doesn't suggest

it was good," Gazzaniga said.

Indeed, historical evidence and tooth enamel analysis suggest that the lower echelons of Roman society subsisted on an extremely limited diet of poor quality, often rotting grains and stale bread.

Indeed, historical evidence and tooth enamel analysis suggest that the lower echelons of Roman society subsisted on an extremely limited diet of poor quality, often rotting grains and stale bread.

No comments:

Post a Comment